The resurgence of management systems theory

TU Delft AR1MBE030: Real Estate Management

Essay on the formation of a generic real estate management theory

03.02.2023

Abstract

This essay reflects on the potential of the resurgence of management systems theory and the potential contemporary application of the theory. Part 1, traces the development of systems theory and its successor dynamic capabilities framework. Part 2, explores the application of dynamic capabilities in CRE, while Part 3 explores its use in housing management. Withing the framework of this assignment, it is concluded that although dynamic capabilities framework does complement certain aspects of CRE, it is structurally unable to frame housing management.

Introduction

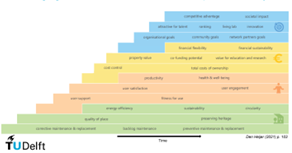

As an important educational component of the course, students are asked to reflect on the possibility of the existence of a broad real estate management theory that is applicable as both CREM and housing management theory. A concept or theory needs to be identified and consequently critically analyzed in its ability to address shortcomings within the sub-disciplines. Important to note are the premises of this course. First, that management seems to exist because the world is not static. Second, that humans have the possibility to shape the course of events. And lastly, that instead of searching for absolute truths, acceptance of relative certainties of present reality form a stronger foundation in the studying of management (Vande Putte, 2020). With this mindset, inspiration for my topic selection is found in both a lecture given as part of our course by van Staveren and in literature by Wijnja et al. (2021). Illustrated in both figures 1 and 2, are references made to an ever more complex process of managing the built environment. If we are to address complexity as: a dynamic force, that is malleable but without a predetermined prescriptive approach, then we are in search of a systems-approach with a paradigm that can encompass their dynamic nature.

In the search of such paradigm, systems theory resonated in me the most. It is defined by Teece (2018) as a holistic interdisciplinary field of study that deals with the nature of complex sy-stems, both natural and artificial. It is concerned with the investigation of the structure, behavior, and interactions of systems and the principles that govern their behavior (Teece, 2018). Systems theory considers a system to be a set of interconnected elements that work together to produce a specific behavior or outcome (Teece, 2018). It aims to understand how the different parts of a system interact with each other, how they affect the behavior of the whole, and how they can be managed and optimized (Teece, 2018). This essay explores the applicability of systems theory in management and its applicability to a broad REM, CREM and housing management theory.

Part 1 – Management systems theory resurgence

To understand where and if management systems theory has a place in real estate management today, a small excursion into its origins is needed. Systems theory was developed in the pursuit of the “unification of science” in the 1950s under the umbrella of management science theory in the post WWII era (Khorasani & Almasifard, 2017; Teece, 2018). It argues that to understand a system, a holistic interdisciplinary approach on the study of a system’s parts interdependencies is needed (Teece, 2018), in other words, the whole is greater than the sum of all its parts. It relies on mathematical, statistical, and quantitative models of interdependencies and feedback loops to explain phenomena (Khorasani & Almasifard, 2017; Teece, 2018). The application of systems theory in management was introduced by economist Kenneth Boulding in an issue of the journal Management Science (Teece, 2018). However, the application of the theory in management was heavily criticized for its overdependency on mathematical models and its inability to provide insights on cause and effect relationships, and the absence of the human element in its design (Teece, 2018). The theory itself was largely phased out by the 1980’s and superseded by the organization environment theory (Khorasani & Almasifard, 2017; Teece, 2018). However, the relevance of systems theory can be observed in its influence of the works of Steiner’s 1979 Strategic process model (Figure 3), and Nadler and Tushman’s 1980 congruent model for organization analysis (Figure 4) (Grant, 1996; Khorasani & Almasifard, 2017; Teece, 2018). Both draw upon the need to identify interdependencies and the establishment of information feedback loops, however this time, incorporating external influencing factors as well as the human element (Teece, 2018).

As alluded in the introduction, the contemporary complexity in organizations is resurging the need for advanced modeling approaches. The early 1980’s management models do not respond well to dynamic complexities. Evidence of this can be seen in Mintzberg’s 1987 Emergent Strategy description. Mintzberg describes the process of strategy derivation as being dynamically influenced by external factors, deviating the outcome from its initial intended version. In comparison to Nadler and Tuschman’s and Steiner’s models, which incorporate externalities into a closed feedback loop model, Mintzberg’s observation properly maps the uncertainty of the influence externalities have on a process. The realization of the need to address the dynamic nature of influencing factors is the current drive that fuels the need for complexity in models. An emerging paradigm to address this challenge is the dynamic capabilities framework (Teece, 2018). The dynamic capabilities framework (Figure 6) stems from systems theory, but addresses its shortcomings by combining path dependency with entrepreneurship to ensure an organizations “evolutionary fitness over time” (Teece, 2018). This means being able to steer the process towards an optimal outcome.

Part 2 – Management to CRE

Teece (2018) mentions, that “the goal of a firm is not just survival, but prosperity.” Although management systems theory is no longer applicable today in its original form, its successor, the dynamic capabilities framework will be used to evaluate its applicability in Corporate Real Estate.

Returning to the five-stages of real estate evolutionary model (Figure 2), Wijnja et al. (2021), describe the necessity of a new sixth stage introduced by Hoendervanger et al. (2017). The sixth stage in CREM refers to a new role for a CRE manager. Together, as taskmaster, controller, dealmaker, intrapreneur, business strategist, the sixth role expands into the discipline of facility management and takes into account both business and user needs, with an user-centered approach (Wijnja et al., 2021). The model suggests increasing levels of professionalism and strategic integration from stage to stage, and it is a framework to benchmark CRE portfolios (Wijnja et al., 2021). In practice, the sixth stage is used as a tool for continuous improvement of CREM, however the framework finds limitations in that it is difficult to self-assess an organization’s current position (Wijnja et al., 2021). It is possible that an organization find itself at different maturity stages for different characteristics, and thus in practice, it is used broadly in effect to steer policy adjustments (Wijnja et al., 2021). The inherent shortcoming of this model lies in its assumption that stages are achieved in bulk, which leads to CRE staff striving for higher stages than what is necessary (Wijnja et al., 2021).

The dynamic capabilities framework approach would change this paradigm, as at is core it assumes a nested hierarchy of capabilities (Teece, 2018). Teece (2018) attributes to the nested capabilities hierarchy the ability for top management to be able to sense, seize, and transform their organizations effectively. The nested paradigm represents the interdependencies and positioning between the different levels of decision-making in CREM and prioritizes them. This is a clearer structure in comparison to a stage-by-stage model. It shifts the attention of CREM from congruence to “cospecialization”, and thus extra value can be conceptualized when a two or more characteristics are used jointly rather than in isolation (Teece, 2018).

Part 3 – CRE to Housing

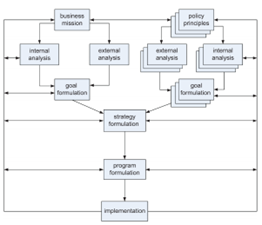

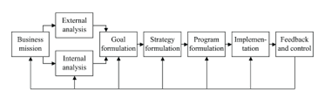

Having established a use case of paradigm shift in CRE using dynamic capabilities framework, an excursion will be made into Nieboer’s (2011) adjusted model of Kotler’s strategic planning process model of 2003 (Figure 7).

Nieboer’s (2011) adapted model is an adaptation of a strategic business planning model into one that fits the current state of social housing in the Netherlands. In its research, key differences between Kotler’s model and Housing management needs were identified (Nieboer, 2011). Conclusions form the bases for the model adaptation illustrated in figure 7. This included a split between business mission and policy principles goal formulations, with both internal and external stakeholders and actors influencing the process (Nieboer, 2011). The unique situation in housing demarked by Nieboer, was that unlike CRE, portfolio policies do not necessarily prevail, hence a consolidation stage of policy and business goal formulations takes place to form a strategy (Nieboer, 2011). Teece’s (2018) dynamic capabilities framework, identifies three external influencing forces: rivals, complementors, and institutions. The concept of rivals can be associated with private housing developers, complementors as residents, activists, and other housing associations, and institutions as government and regulatory bodies. However, there is a key difference between Nieboer’s model and Teece’s framework, in that for housing actors can have their own policy principles and their own analysis. Hence, unlike Teece’s framework, external actors play an active role in the shaping of a strategy. In contrast, the dynamic capabilities framework assumes that a manager can adjust all its internal organization in accordance with external influences, however the external influences remain outside of the organization. This critical distinction makes dynamic capabilities unfit in certain paradigm aspects with housing management, as its framed towards achieving competitive advantage with sustain longer term high performance (Teece, 2018). Whereas a housing association may not necessarily think of competitive advantage as criteria for their strategy formulation.

Conclusion

As I started this journey, I wasn’t sure what systems theory was about, as I have only heard of it being mentioned primarily from computer science. A reference to it was made in one of my literature reviews while looking for a topic for this essay that sparked my curiosity. It is clear to me that the DNA of systems theory is still present in many of the models we reviewed through this course, however its mechanical nature and development primarily within the natural sciences fields, restricted its potential as a social science tool. It is evident that many scholars have tried to carry these concepts forward into management, most recently Teece, which came to my attention only while researching this essay. The integration of the human element into its paradigm has been the primary pursuit of Teece’s dynamic capabilities framework, however as the basis for an all-encompassing broad RE management theory, I conclude that it is not a good fit. Although Teece concludes in his 2018 paper, that dynamic capabilities framework abstains from directly invoking systems theory, he does mention that “the two approaches are concordant.” The dynamic capabilities framework brings the human element to systems theory, however not enough of it. It is, however, a good endnote to mention the introduction, this course was not the search for an absolute truth, nor was this assignment. Rather, the acceptance of relative certainties. Dynamic capabilities and systems theory do have an influential component in the academic discord of real estate management, and with increased complexity, layer cakes of paradigms built on top of one another. Their past paradigms influences remain.

Resources

Grant, R. M. (1996). Toward a knowledge-based theory of the firm: Knowledge-based Theory of the Firm. Strategic Management Journal, 17(S2), 109–122. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250171110

Khorasani, S. T., & Almasifard, M. (2017). Evolution of Management Theory within 20 Century: A Systemic Overview of Paradigm Shifts in Management. 7(3).

Nadler, D. A., & Tushman, M. L. (1980). A model for diagnosing organizational behavior. Organizational Dynamics, 9(2), 35–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/0090-2616(80)90039-X

Nieboer, N. (2011). Strategic planning process models: A step further. Property Management, 29(4), 371–382. https://doi.org/10.1108/02637471111154818

Teece, D. J. (2018). Dynamic capabilities as (workable) management systems theory. Journal of Management & Organization, 24(3), 359–368. https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2017.75

van Staveren, D. (2023, January 11). Multi-objective optimisation: Dealing with trade-offs in Real Estate Management [Academic lecture]. Lecture REM module, Delft University of Technology.

Vande Putte, H. (2020). Management definition (Extract from Lecture Notes AR1MBE010). Delft University of Technology.

Wijnja, J., van der Voordt, T. J. M., & Hoendervanger, J. G. (2021). Corporate real estate management maturity model. In R. Appel-Meulenbroek & V. Danivska, A Handbook of Management Theories and Models for Office Environments and Services (1st ed., pp. 13–24). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781003128786-2